It took recent articles celebrating the 20 year anniversary of Perfect Dark to jolt my memory back to those times. Perfect Dark was Rare’s highly anticipated follow-up to the ground-breaking GoldenEye, both on the Nintendo 64. I was 16 when it was released. I don’t remember the game as well as I should, considering that at the time I was running, along with my brother Jake and best friend Alex, what was probably the most popular Perfect Dark fan site in the world.

Previously, I’ve always left my nostalgia there: a hazy feeling of pride for something created in a time long gone. But this time I’ve decided to return. I’m using the wonderful Wayback Machine from the Internet Archive to revisit PDark.com in its glory days. I feel like I’m diving down to the depths, to shine a torch around an old sunken wreck.

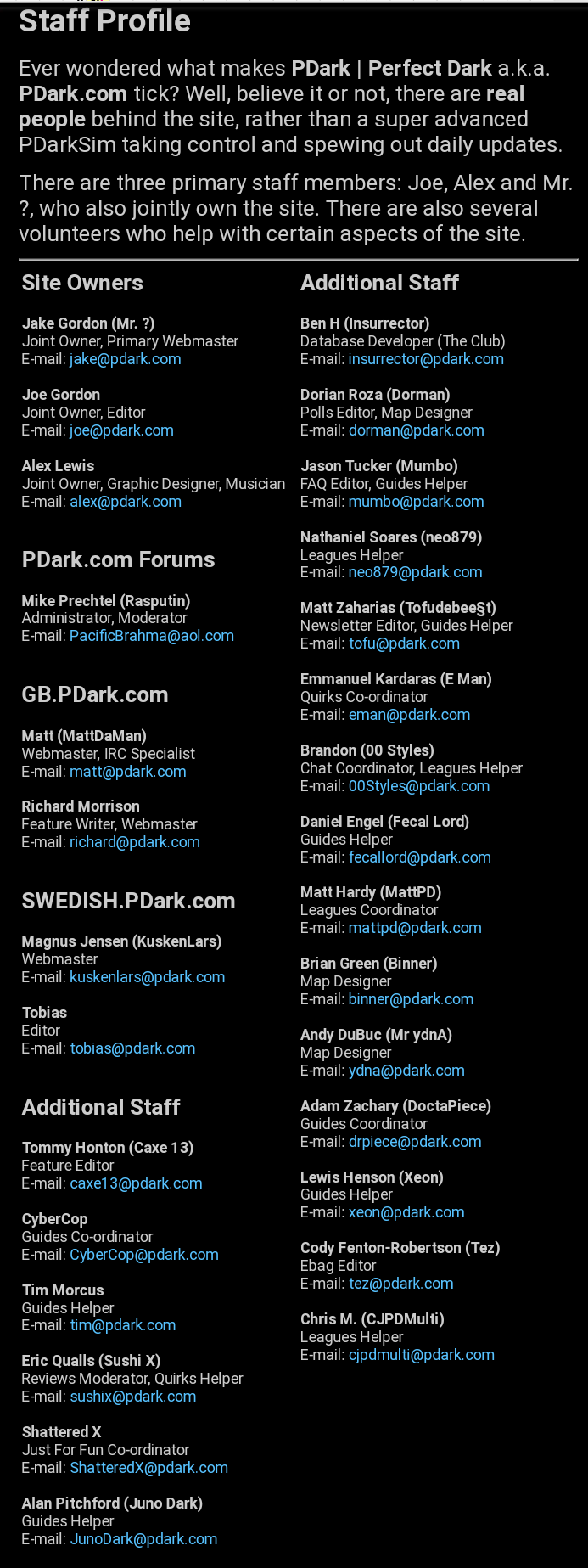

This is one of the first specimens I’ve dredged up:

I barely remember that we had any volunteer staff members, never mind an army of 26 of them (and I mean no disrespect to any of them: at the time they meant the world to us). When I show this to Alex it is clear he has forgotten too. “We peaked too soon,” he says. He means that now, at 36, neither of us has an extensive list of staff working under us, like we did when we were 16. He means that our site clearly was a big deal, once.

I hope that looking back at it sheds a light on how gaming fans used to experience the internet during that period. For every big game that came out there were dozens of sites just like PDark.com, and these sites meant a huge amount to a great number of people.

In the summer holidays of 1999, Alex and I – both 15-years-old and best friends – were still high off the success of selling 80 copies of our 150-page The Golden Files (“Crikey… Not so much a fanzine as a frighteningly comprehensive homage to GoldenEye.” – The Fanzine Farm, N64 Magazine, April 1999). Jake – our senior at 17-years-old – suggested we make a site for Perfect Dark. We needed no convincing. It is hard to believe now, but at this point Jake was the only one of us who had the internet (he kept it in the box-room of our family home). We poured our hearts into the site over the next few months: Jake coding, Alex creating artwork and music (our site originally had a MIDI soundtrack), me writing previews and articles like ‘GoldenEye vs. Half-Life’. Soon we had a steady stream of visitors and emails coming in.

And we loved it. It gave all three of us a seemingly limitless creative outlet. There was no formality to how we did things, and there is no evidence we were bothered about having to keep up with schoolwork at the same time. In an article I wrote in November 1999 I summarised our experience: “And it is outrageous fun, making such a site, getting such responses and knowing that what could be the best game ever made is that little bit more documented and hyped up.”

Looking back over my writing is cringey AF. I was a geeky adolescent boy writing mainly for geeky adolescent boys, aping the style of gaming mag journalism at the time: at least 3 attempts at comedy per sentence, buckets of hyperbole, with awkward elbow nudges of surrealism, pranking and baiting. But what our updates lacked in quality was made up for by enthusiasm and regularity. As Jake remembers: “I think we tried to update every day, even if there was no news… and I’m sure there was no news on most days.”

If you were a gamer in 1999, you probably spent a lot of your time on sites just like PDark.com. Nowadays if you’re interested in a game you might check out a wiki on Fandom for the facts, YouTube for some tutorials, Reddit for the funny discussions – not to mention the Twitch streams. None of these existed back then. Yes, there were commercial sites becoming established, like IGN and GameSpot, but these were competing with game-specific fan sites – typically run by teenagers from their bedrooms – that often attracted more devoted followers.

What did fan sites mean to a games company like Rare at this time? Very little, it seems. I had the good fortune of talking recently with one of Perfect Dark’s original designers, David Doak. It didn’t surprise me that the designers of Perfect Dark hadn’t spent much time following fan sites, but it did surprise me just how unimportant the internet in general was to them at the time.

David recalls: “Nobody had the internet on their desktops at Rare. It was kept in a locked box basically – in ‘the internet room’. I particularly remember an announcement from Square that Final Fantasy would go exclusive for the PlayStation. I’d seen it on some forum and I’d mentioned it to someone. Then I had Tim Stamper [one of the founders of Rare] phoning up and saying, ‘How did you know about that?’ He knew about it himself because he’d heard it directly from Nintendo. He hadn’t realised the news had spread over the internet within a few hours. They had very little perception that that channel existed.”

Albeit of little concern to Rare, the flourishing ecosystem of fan-sites around Perfect Dark was growing, and it was connected together by all-important Links pages (here’s a late example of ours). Looking back at my updates, I seemed obsessed with editing our links and curating our list of ‘Affiliates’ (they got their colourful banners up too!). Jake explains: “Search engines were different then. This was before Google. I spent a lot of time getting us good positions in search engines, but people used search engines far less, sticking more to sites they knew and what those sites recommended. And you’d boost your search engine rankings by swapping links with others. There was also a ‘Perfect Dark Top 25 Gateway’ that we got a lot of our traffic from and we tried our best to game.”

I adored this sprawling community of like-minded content creators. But an inevitable consequence of close relationships with rival sites was the occasional feud. For example, in January 2000 we updated: “Don’t Be Fooled Guys: By PD Central’s propaganda ploy that is. They have been rumouring at an ‘exclusive interview’ for some time now [with Rare], although all I want to say is that we’ve had evidence to suggest the claim can’t be backed up.” There was backlash and fans took sides. As we forged allegiances and enmities, dramas played out like WrestleMania. (For the record: PD Central did finally get that interview.)

A rapid increase in connectivity was a crucial feature of this time. The internet was in the process of transforming from being a collection of static resources (in our case: guides, screenshots, editorials etc), to a place of relentless interaction. When we started PDark.com we were probably thinking: ‘what a funky way to publish a fanzine!’ By mid-2000 it was something else entirely: a living, breathing community.

You can see this development in the features we added over time. Near the start, from September 1999, we ran weekly round-ups of replies to emails that were sent in (and there were many). Notice how at this time we were very much the gatekeepers of interaction: all discussions went through us.

This was not dissimilar to what gaming journalism had looked like in magazines since the 1980s. David Doak reminisces: “When I was growing up, as a teenager, we had a ZX Spectrum. There was obviously no internet. But a lot of the format of the magazines like Crash was very much: a letters page and people asking for cheat codes and help. Then when we move to something like your fan site, that becomes like a church newsletter or something. Someone’s gathering stuff up and sending it out. It’s got its own community but it doesn’t work peer-to-peer, it’s centralised. You’re moderating it.”

David also remembers how, at the time of Perfect Dark, magazines were still more important to game developers than websites, but this was in the process of changing: “N64 Magazine, Edge Magazine – a lot of us were avid readers of Edge. It meant a lot to us in the GoldenEye team when it got a good review in Edge. But with mags there was always a big latency: the time to print. That’s why getting information gradually made that shift to being online, because the web’s ‘time to print’ is just so much faster and immediate.”

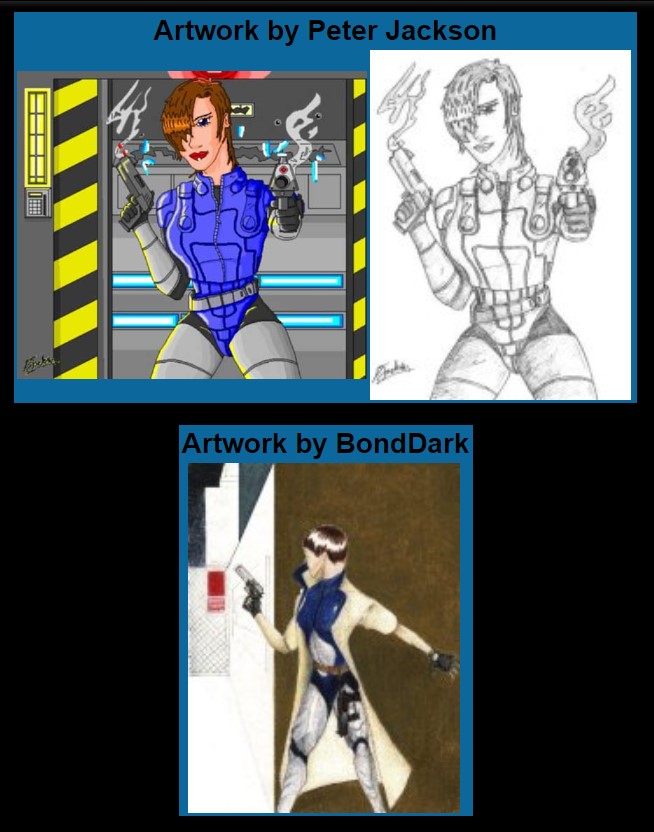

Another traditional method we used for keeping the community engaged was running competitions like ones for Perfect Dark fan-art and fan-fiction.

To increase interaction we experimented with ICQ chat sessions (“we’re mainly online between 6pm and 12pm GMT”) and in December our own PDark.com Chatroom, using a Java applet and mIRC.

In April 2000 we gave visitors the ability to post comments to our news updates. This was an instant hit. This feature – now ubiquitous – was clearly new and exciting for most of our visitors. (For something that now seems universal, it’s surprising to note that posting comments only appeared on the web in 1998.)

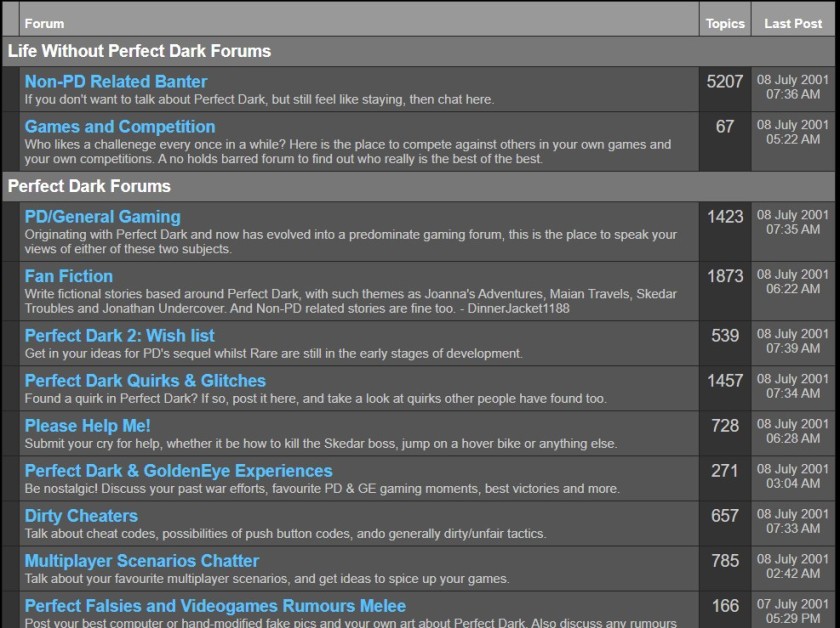

But it was our forums that became the beating heart of the site. We experimented with many different platforms for message boards (such as EzBoard and vBulletin) before settling on using an Ultimate Bullet Board. This provided a fluid user-to-user experience (again, now ubiquitous) that was a far cry from the ‘wait until they publish a weekly roundup of our emails…’ that had characterised our site just months before.

It is amazing we all found so much to talk about. The game – much-delayed – was still very much not out. New info from Rare was in scarce supply, but the scraps that we threw to our ravenous visitors were savoured and their bones picked over. Little did anyone know at the time that we had in fact played a pre-release copy of Perfect Dark at the offices of N64 Magazine – but had been sworn to secrecy.

By April 2000, with the final Perfect Dark release date one month away and anticipation reaching fever pitch, the site had become so popular that we put out a call for volunteer staff members. We had so many applicants that we couldn’t create new roles for all of them. With the extra help we continued to provide more modes for users to interact with each other.

Even before the game launched we opened a League for speedrun times. Shortly after that we opened The Club: “a fully searchable database of people such as yourselves, enabling you to find people of similar abilities, living in similar areas, or of similar tastes. Like a dating agency, but with the dating taken out, and possible PD-meets arranged instead.” (Created by Insurrector.)

Perfect Dark finally landed on 22nd May 2000. We declared it “The Start of a New Generation.” Our site saw a surge in activity, with thousands of ecstatic gamers flocking to our forums to share their first impressions.

Activity in the forums grew rapidly. By August 2000, when everyone was still squeezing what they could out of their treasured game cartridges, we were already reporting that moderating the forums was becoming unmanageable. Not only were hundreds of threads active on Perfect Dark-related topics (for example, we got over 700 entries to ‘Signs You’ve Been Playing Perfect Dark Too Long’), but there was an even more popular ‘Non-PD Related Banter’ forum with thousands of topics.

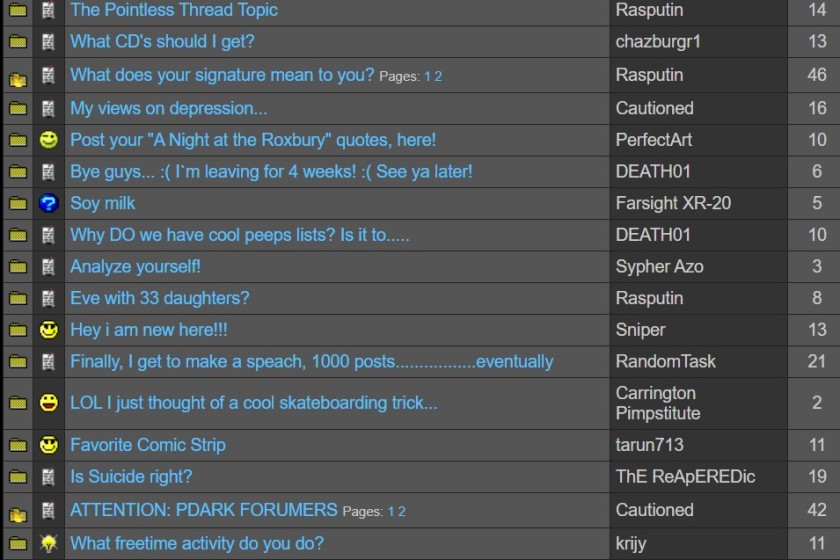

By the end of 2000 we had over 4000 regular members. They talked about anything and everything – just take a look at the screenshot below for a sample of topics. It wasn’t always mature, and it sometimes made too much reference to masturbation, so we had to recruit a network of moderators, led expertly by a staff member called Rasputin.

Something that seems to me astonishing, looking back, is that when we published things on our site we did so without any concern at all about privacy, legal issues, opening ourselves up to online abuse, and all that stuff that we (rightly!) teach kids about from primary school today. Yes, we tried to keep things positive, but there simply wasn’t the concept that you had to be worried about what ‘digital tattoo’ you were burning onto yourself. As Alex says, “In many ways the internet used to be a better, more naïve, more optimistic place, didn’t it?” Even our forums, which were a real wild west of sweaty teenage discourse, didn’t really worry us.

The whole experience of ‘going on the internet’ was so different back then. It felt like a big, fun optional extra, where you immersed yourself in games and hobbies, and chatted with friends and strangers. The web hadn’t yet wrapped its tendrils around every aspect of ordinary life.

It’s also undeniable that PDark.com has a special place in our hearts because of the time of our lives: we were young, we were growing up, we had few responsibilities, and everything felt fresh. There will be similar groups of young girls and boys now, tinkering with new ways of using the internet to build communities of their own.

So how did PDark.com end? In my trawl of old updates it now seems clear that there was a long fizzling out, with a few nasty bangs along the way. Despite everybody’s rave reviews of Perfect Dark upon its release (including ours: “The last was golden but this might just be perfect…”), we weren’t kept enchanted by it like we had been by GoldenEye. We’d probably been having the most fun in the run up to Perfect Dark’s release, when we and our users had been salivating for more info. The web was also a ropier place than it is now; we suffered awful server crashes, losing tons of content. Another serious issue was that, as Jake told our users in February 2001, “the banner advertising bubble has well and truly burst.” Up to that point we’d been a member of Gamer’s Alliance, which provided hosting and gave us much-appreciated pay-outs, but no longer.

We tried to transition into a general Nintendo fan site (Ninten.com) but that never took off. We were also growing up: Alex and I were finishing our time at school, Jake was going travelling for 6-months, and I don’t think we really had the appetite to keep going. In May 2001 I wrote, “Thank You… and Sorry: ‘sorry’ for not fuelling all of PDark.com to grow and prosper as much as the Forums… I just felt like congratulating all of you on supporting (or at least exploiting) us at PDark.com… We’ve developed a community in itself.” I also wrote, “This isn’t a good-bye,” but, looking back, it pretty much was.

Alex now has mixed feelings about that time: “I remember knowing that we were somehow important to people. And there’s no doubt that doing PDark.com made a huge impact in getting us where we are today in terms of creativity and careers. But I feel a little embarrassed looking back on what we used to write and the artwork I used to make. We were young, we were naïve, and we somehow thought that we could compete on an international stage without much experience. I think there’s a parallel there with the creation of GoldenEye itself – the young team at Rare were just throwing themselves into it, fuelled by ambition and excitement, fudging things as they went.”

The internet is now a very different place, both for fans who want to create content about the games they love, and game designers who are paying more attention. David Doak captures this fascinating transformation: “It started with games creators making stuff, very much in isolation, which then went out into the world, and people interacted with it and critiqued it. Then the internet enabled the speed of that feedback loop to increase, and for anyone to talk to anyone, so you got forums and blogs and fan sites like yours. Now, at the other end of that trajectory, we have influencers. It’s incredible: we have these hyper-fans who have become influencers – on YouTube or Twitch, for example – and the games companies go to them for validation.”

David continues, “These hyper-fans control where the gaze goes. I don’t think it’s a very healthy culture. When you were working on your Perfect Dark site you were the hyper-fans of that era. At that time, games companies could afford to pretty much neglect you. But the people who are the hyper-fans now are sitting in a very different place!”

I’m not that proud of some of the stuff that’s up on the archives of PDark.com. I don’t love the writing style I had then. I can’t look at every forum thread and argue that this was humanity at its finest. But I’m still proud of what we achieved: of building that community. And to me the significance of this lies in the absolute insignificance of PDark.com itself: there were thousands of communities just like this springing up across the world in those heady days of the early internet. It was a hell of a place to grow up.

Many thanks to David Doak (now Lecturer in Games Art and Design at Norwich University of the Arts) as well as Jake, Alex, and all the other 26 staff members of PDark.com.

Hahaha, what a find after doing some nostalgia-searching. Better times! – Richard Morrison, feature writer / webmaster, gb.pdark.com (I really should add those my CV…)

Amazing to hear from you, Richard! Glad you found this piece and it brought some happy memories back.